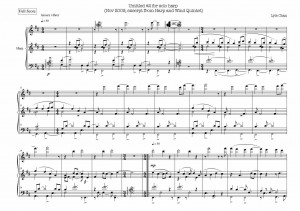

Untitled #2 for solo harp is not called such because there is an Untitled #1, but because it’s the 2nd version of the piece.

The piece was begun in November 2009 as a birthday gift for my friend, teacher and colleague Amir Zoghi. I wanted to give it to him at this beach party, but the version I had completed did not, I realized in time, ring with truth. And if there’s one thing art should do, it’s to ring with truth.

It wasn’t that the piece was missing anything. It was the opposite: it contained a lovely bell-like motif that shouldn’t have been there, as it turned out. I had become attached to this little thing. I tried to wrestle it into this nook or that cranny, hoping to find a spot in the piece where it could just be beautiful quietly. Yet no matter where it got put, it kept knocking things over with its mysterious, large aura.

Finally I took it out. It now sits on two bars of manuscript paper, seemingly content to amuse itself until I come back for it one day. I can’t imagine I will be very long.

The beach party came and went. My Czech boyfriend Petr came to visit from Prague. He comes to see me once a year. By coincidence or not, the last time Petr visited I was working on a very similar piece.

It was called Untitled, for Steve for solo piano. It was written for Steve Pavlina, who like Amir has been a profound teacher for me in my personal growth. Both pieces are built on moment-by-moment form, without explicit architecture. Each moment exists with no dependence on the moment before or after. This form is somehow a musical expression of what both Amir and Steve advocate: living fully in the present moment, not the past which is irrevocably over or the future which is only as real as fiction.

I think of the piece as being in 5 moments or sections of very unequal lengths. I am extremely happy with 3 of the 5 sections. I am very happy with a fourth, and I am sufficiently happy with a fifth. This was interesting to me: why didn’t I keep writing until I was equally happy with all 5 sections?

I stopped because I sensed the music itself was satisfied. Any lack of satisfaction on my part was only because I feared the music smacked of an insufficiency of originality, even of cliché. But this is where the artist easily falls into a trap. Insisting on originality is an egoic posture. The egoic artist says my art reflects on me and so I must make it do what I want. Whereas the truth is we artists are taken on a process of discovery to find what the art wants and we execute that. As Auden said, an artist need be concerned not so much with originality as with authenticity.

When I am happy with something I’ve written, it is often tied up with a sense that it is unrepeatably good. I feel I may never write something that good again. Of course, this is a limiting belief I have proven wrong time and time again. And yet I somehow look forward to having this feeling, as if it omens my contentment. There is an inexhaustible well of Good Ideas from which we artists draw, but we often mistake our own exhaustion for that of the well.

One day I played the piece to my friend David. The section with double octaves instantly transported him to the film Gerry and the long, wordless driving scene scored entirely with Arvo Pärt’s Spiegel im spiegel. I thought nothing of this, until weeks later when it dawned on me the reason the Pärt connection exists.

When I was writing Untitled, for Steve in December 2008, Pärt’s ‘Silentium’ had drifted to mind. I can faintly hear its presence in Steve’s piece. One year later, a residual essence of this visitation was triggered when I was writing under similar circumstances: I was in Petr’s company, writing in moment form, and intending the piece as a gift for a great teacher. Though I can’t hear any Pärt at all in Untitled #2, it’s quite pleasant to be constantly reminded of the inseparability of, truly, everything.

Lyle Chan Music

Mar 2010

{ 1 trackback }