A slide from ‘Day Of The Hivid’, 1992

A slide from ‘Day Of The Hivid’, 1992

At the time I wrote the memoir essays that accompany Dextran Man, Part 1 and Part 2, there wasn’t much interest about buyers clubs for HIV/AIDS drugs. The movie Dallas Buyers Club hadn’t been released yet, and coupled with the general forgetting of the AIDS epidemic over the preceding 15 or so years, buyers clubs weren’t really known outside the community that had used them.

But now, due to the recent uptick in willingness to remember (amongst us who lived through it) and inquisitiveness (amongst historians and documentary makers who didn’t), people are curious about this phenomenon of patient self-empowerment.

I do get asked from time to time for details of how the Sydney buyers club was run. And the mainstream media get disappointed by the answers. They have this notion that it was romantically cloak-and-dagger. Playboy magazine interviewed me in 2013, a few months before the release of Dallas Buyers Club. Then the writer said the publication didn’t want to run the interview because it wasn’t what they’d thought. I hadn’t made mules swallow condoms filled with drugs. I’d just booked FedEx.

So, I thought about how to give out the details, and I’ve concluded that the best way is to publish a document from that time.

This address, Day of the Hivid, was delivered at the 5th National Conference on HIV, held in Darling Harbour, Sydney in November 1992.

But it began as a talk I gave to staff at Roche Products, the Australian subsidiary of the multinational pharmaceutical giant Hoffman La Roche, which owned the drug ddC.

The talk came out of my relationship with a product manager there named Michael. At the start, the relationship was a little adversarial, but it ultimately led to a cooperation for which I was grateful, because it rescued my buyers club clients at a bad time. I‘ll come to that.

Michael was about my age, early to mid twenties. I knew he was sent by Roche to be my ‘friend’ and keep an eye on me, the person importing bootleg versions of their proprietary drug. Our first conversations were tense. We disagreed about a clinical trial called Delta, which was the European and Australian wing of a trial known as ACTG175 in the USA.

Roche had been pushing enrolment of Delta, which it continued to do even as late as mid 1992. Its purpose was to compare AZT monotherapy to AZT in combination with either ddI or ddC. I said to Michael, but we already know the answer: combination therapy is superior to monotherapy. We know this from the buyers clubs: nearly a year of experience with patients who were using bootleg ddC combined with AZT obtained officially.

Michael said, our scientists tell us it’s not enough to rely on anecdotes; we need to prove this. I said, then prove it in an ethical way. Delta’s trial design forces some people to use AZT monotherapy, which is below the medical standard of care. Delta is unethical.

He was a good listener, I’ll give him that. He was genuinely fascinated by this defiance, this unorthodoxy of patients not doing what ‘experts’ told them but thought for themselves – and acted on it too, creating an underground where people broke the law to get treatments for themselves.

Michael admitted that he learned more about ddC from the underground than from Roche itself. At work he only got information that had been published or presented at conferences, whereas the activists had anecdotal information from patients and their doctors. Before the trials proved it, we all knew that the combination of AZT and ddC was superior to AZT on its own.

Proof is a laggard. It is the last to arrive, after theory and belief, and lagging was what we could not put up with in life and death situations. Civilization is replete with tales of people knowing things to be true but were proven right only after they had died. Twenty years before Louis Pasteur proved that microbes caused disease, Ignaz Semmelweis was castigated by his colleagues for outrageously suggesting that their hands were dirty and should be washed before performing surgery or aiding childbirth. In all the clamor for evidence-based medicine or even climate activism, this is something to remember. That something was already right before it was proven right.

It wasn’t really me who swayed Michael. He got there himself, by sheer poundage of the evidence once someone put it in front of him. Michael said he was doing his best to argue the case of the buyers club to his bosses, who thought he was being coopted by dirty activists. So he said, if I get them in a room for an hour, will you come talk to them?

And that’s when I came up with the first version of Day of the Hivid. That version stopped in mid 1992, whereas this second version continues into November 1992, after ddC was approved in both the USA and Australia.

So here it is, the speech that I delivered at the 5th National Conference on AIDS, 4th Annual ASHM Conference on the Medical and Scientific Aspects of HIV/AIDS, Darling Harbour Convention Centre, Sydney, 22-25 November, 1992. I don’t remember which of those days it was, but for some reason, I seem to recall it being a Tuesday. I used slides, not reproduced here, but these did not contain any information that was not in the speaking text.

I have chosen to call today’s presentation The Day Of The Hivid, in homage to the adorable tradename given by Hoffman La-Roche to their drug ddC. ddC will feature prominently in the presentation.

Today I will do three things. Firstly, I will recount the history of the so-called underground movement, both in the USA and in Australia.

Then I will discuss the activity of the Buyers Club at the AIDS Council of NSW, and attempt to explain why the activity has centred around ddC, instead of any other drug.

Finally, I will provide my view of why buyers clubs became necessary in the first place, and how Australia’s grossly inadequate clinical trials and drug regulatory systems are forcing buyers clubs to maintain their existence.

[slide (not shown here)]

But before I begin, I want to thank some people for their assistance in my work. I am indebted to the staff of the AIDS Council of NSW for their support in the buyers club, Mr. Jim Corti for his pioneering work in buyers clubs, and the international ACT UP network for having the guts to stand up to insane and deadly drug regulation wherever it exists. Thank you. You are my inspiration.

[slide (not shown here)]

The AIDS underground drug movement began in earnest in 1984. AIDS was then a phenomenon only 3 years old. The discovery of the causative agent, later named HIV, had only been discovered a few months earlier. Few compounds had been screened for anti-HIV activity and AZT, then called Compound S, was still confined to the test-tube. In desperation, people with AIDS in California drove across the border to Tijuana, Mexico to purchase two drugs which were unlicensed in the United States but available over the counter in Mexico. The two drugs were ribavirin, a purported antiviral, and isoprinosine, a purported immune enhancer. It made intuitive sense that a virally-caused immune disorder should [be] combatted with the combination of an antiviral and an immune-enhancer.

Many people with AIDS were unable to make the trip to Mexico, especially if they lived any further than California. Thus, buying groups were organised, where a small number of people would undertake the hazardous journey across borders, armed with cash from a large number of potential buyers.

Even though this therapy was later discredited, the experience had set the scene for the large scale smuggling of unavailable drugs into the United States.

In 1985, dextran sulfate became the focus of attention following the Ryuji Ueno report showing that the compound could inhibit HIV infection of the CD4 cell. Dextran sulfate was available over the counter in Japan. Because this was a country far less accessible to Americans than Mexico, buyers groups had to organise in an even more sophisticated manner to obtain a compound that had to be smuggled through airport customs instead of in the back of a car.

Unfortunately this therapy was also later discredited.

In 1987, the underground took a large step forward. Following a report by Robert Gallo in the New England Journal of Medicine on the activated lipid compound AL-721, buyers club operators searched in vain for a supplier. This was not surprising, because AL-721 was a novel compound in preclinical study that was not licensed anywhere. So buyers club operators, for the first but certainly not the last time, resorted to manufacturing a a drug.

Fortunately, the manufacture of AL-721 involved nothing more than following a recipe for combining egg lipids, and required apparatus no more specialised than could be found in an average kitchen.

AL-721 was later discredited as a treatment.

In 1989 the strange and unexplainable drug Compound Q was imported from China. Compound Q, the active ingredient of which is trichosanthin and is derived from a Chinese cucumber, was first shown by the University of Hong Kong to be cytotoxic to HIV-infected macrophages. Frustrated by the lethargic clinical trials system, the underground took a bold step forward and began conducting clinical trials of Compound Q. The results were later published in the Journal of AIDS and Compound Q remains today the subject of clinical investigation.

Finally we come to 1990 and the most famous underground drug of all, dideoxycytidine. In 1990 preliminary reports suggested that combination therapy with AZT and ddC was superior to AZT by itself. Consequently, activists approached ddC’s manufacturer Hoffman-La Roche for wider access to ddC. Hoffman La-Roche refused, and so the underground began manufacturing ddC.

[slide (not shown here)]

Australia’s involvement in the underground mostly began in February of last year, when the Therapeutic Goods Act, a piece of legislation that governs the distribution of drugs, was amended to allow personal importation of drugs not approved in Australia. Personal importation limited the amount of drug to 3-months’s supply at a time, and the importer must have a prescription from a physician registered in Australia.

And so in May 1991, the AIDS Council of NSW formed its buyers club, officially named the Treatments Access Scheme, taking advantage of the newly-relaxed legislation. ddC was imported from several sources including New York, San Francisco and Dallas.

By June of 1991, there were over 3000 people using buyers club ddC in the US, and 40 in Australia. Also in June, the interim analysis of the clinical trial ACTG 106 was presented at the VII International AIDS Conference in Florence, Italy, causing demand for ddC to skyrocket beyond supply. Consequently, the suppliers ran out and Australians were among those who had their supply cut off.

[slide (not shown here)]

In late July of 1991, manufacturing was escalated to extremely large quantities and the Australian supply resumed, importing from a new source in Los Angeles.

In late September of 1991, Roche Products in Australia begins a two-dose, open-label ddC monotherapy program. A few buyers club clients joined the open-label program, and in spite of the fact that they were not supposed to simultaneously use AZT, they did.

In February of this year, a tragedy occurred. The US Food and Drug Administration, in their investigation of the US buyers club, found a number of batches of ddC with potency variations. They found that the ddC capsules contained between 0 and 200% of the stated dose. The distribution of ddC in Australia was immediately halted as a matter of precaution, even though Australia did not receive any of the batches identified as faulty. In response to FDA urging, Hoffmann La-Roche announced that they would begin a new open-label program which allowed ddC to be used with AZT. Three weeks later, buyers club ddC distribution resumed with a new manufacturer and much tighter quality control.

[slide (not shown here)]

In July, the United States gave approval for ddC to be licensed in combination with AZT, and thus the manufacture of underground ddC ceased, closing the most significant chapter yet in underground history.

However, the US approval of the drug simply caused the access situation in Australia to worsen. With the US source of underground ddC nonexistent and Australian approval of the drug nowhere in sight, Australians on ddC faced a very real prospect of having their supply permanently cut off. So Roche Products, ddC’s official manufacturer, was approached to provide the buyers club clients with ddC, which they generously did and for which I am extremely grateful.

Then in August, the Therapeutic Goods Administration in Australia gave limited approval for ddC to be marketed. Their approval, however, forbade the drug to be used in combination with AZT, and only allowed it to be used by itself. This was no help to buyers club clients, because everyone was using ddC in combination with AZT.

Under pressure from activists, the TGA reconsidered its decision, and in what must be the most bizarre drug approval in living memory, the TGA approved the use of combination therapy in such a way that still meant that the 400 people on the drug will have their supply cut oft. The subject of ddC approval is one that I will return to, with a vengeance, later.

But now, let me give you some details about the operations of the ACON Buyers Club.

[slide (not shown here)]

After consultation with medical and legal advisers, the AIDS Council assembled a little kit to facilitate the importation of ddC. The kit fastidiously documented the role of the AIDS Council as a mere facilitator of the process, with the label of ‘importer’ falling cleanly on the shoulders of the individual client. The kit contained an information leaflet, an informed consent form between client and physician, an informed consent form between client and the AlDS Council, a prescription from the physician, and a medical letter to Australian Customs Service, to be signed by both physician and client.

The prescription and letter to Customs were sent by facsimile transmission to the supplier, and the package, containing drug, letter to customs and prescription was sent to the AIDS Council. The clients would either pick up the drug at the AIDS Council or it would be sent to them.

[slide (not shown here)]

The buyers club has served over 700 clients, of which 400 have come back for at least a second supply. A total of 61 physicians have prescribed through the buyers club, almost all of are general practitioners. Needless to say the geographical distribution of client and physician is identical, and every Australian state and territory is represented in the client list except Tasmania. The vast majority of clients are from the inner Sydney area.

[slide (not shown here)]

I want to turn your attention briefly to the question of why ddC has become the buyers club success story.

I argue that, at the time, ddC was the logical first drug. It came from the family of drugs known as nucleoside analogues, a family from which we had already seen two examples: AZT and ddi. ddC had completed definitive Phase I testing looking at toxicities, and was well into Phase II studies, looking at efficacy. Therefore the toxicities were well-mapped and predictable. So here was a drug on which a lot of information existed, unlike previous buyers club drugs which, although demonstrated to be safe, had no clear efficacy data. Hence, taking ddC as prescribed could do relatively little harm, and could potentially do a lot of good. Buyers clubs in Australia could confidently do soft advocacy for ddC in a way that it could not do for potentially more toxic drugs such as Compound Q or drugs where efficacy was not well established, such as the TIBO compounds. ddC was the perfect candidate with which to begin a buyers club in Australia.

And very importantly, ddC was a simple compound that was easy to manufacture. Unlike the notoriously difficult AZT.

I now want to turn to the role of the underground in treatment of HIV illness.

[slide (not shown here)]

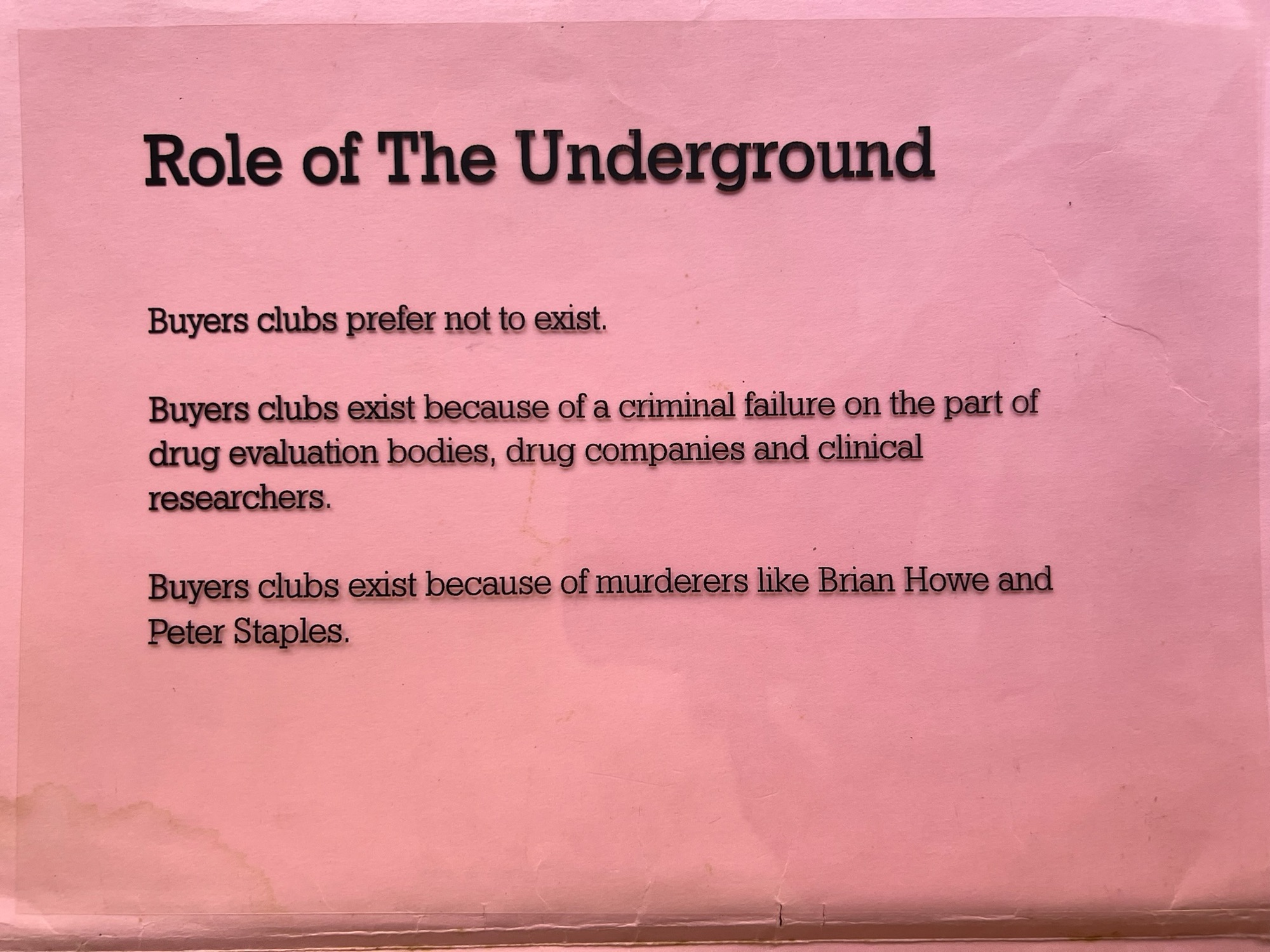

The first thing to recognise is that a primary goal of the buyers club is to do away with itself. Buyers clubs prefer not to exist. But buyers clubs do exist, because of a criminal failure on the part of people whose job it is to provide drugs for people with life-threatening illnesses – drug evaluation authorities, drug companies, clinical trials researchers, etc. Buyers clubs are the result of carrying the empowerment of PWAs to its logical conclusion. If you won’t give us a drug that might save our life, then we’ll make and distribute the drug ourselves. Swallowing a bootleg pill is a political act of the most subversive kind.

I want to illustrate my frustration with Australia’s drug approval system. To do that I will return to the subject of approval of ddC.

The combination of AZT and ddC was approved in Australia only for people with a CD4 count of less than 200, and who have less than 12 months prior AZT use. These limitations placed on the approval are so exclusive that it means every single person who is on the combination right now will no longer be able to get the drug.

Let me explain. There are over 400 people on the combination in this country. They are receiving therapy either through the Roche open-label programs or through the buyers clubs. These two schemes are scheduled to irreversibly terminate as soon as ddC is licensed, if not earlier. However, all 400 people on combination therapy now have more than 12 months previous AZT use, and so are disqualified from having combination therapy. Therefore, all 400 people will have their therapy cut off.

How did the TGA arrive at such a bizarre approval, especially one which in no way resembles the approval given in the United States? I don’t have an answer to that, and perhaps Dr. Geoffrey Vaughan who speaks after me will shed some light on the subject. But now, let me demonstrate that the Australian approval is not supported by scientific evidence.

[slide (not shown here)]

Let’s examine the two approval ~~indications~~ restrictions one at a time. First, the CD4 count. Roche Products applied to have the CD4 cut off at 300 cells. However, a TGA evaluator, using a statistical manipulation with ~~dubious~~ questionable validity, showed that the entire antiviral effect was carried by people with less than 100 CDs. So, 300 CDs on the one hand, 100 on the other. What did TGA do? It compromised on 200. Yes, this is as scientific as it gets.

Let’s now look at previous AZT use. Roche applied to not have any restrictions on previous AZT use. However, the clinical trials were all conducted in people with less than 3 months previous AZT use. So, no restriction on the one hand, and 3 months on the other. What did TGA do? It compromised at 12 months. So you see, there is simply no scientific support for what the TGA did.

So I hope you understand my frustration when I have to deal with such quackery. I am trying very hard to prolong the lives of my 400 clients. I have repeatedly called Minister Peter Staples’ office to alert him to the situation but my pleadings have been ignored. I am calling on Minister Peter Staples and Minister Brian Howe, our two federal health ministers to revise the approval of ddC so that my 400 clients can get the drug. I am now showing Ministers Howe and Staples how they can easily prolong the lives of these people. To ignore this plea is tantamount to murder. Please do something.

There was one disingenuous thing in my speech. I pressed the point that in the gap between US approval and Australian approval, Australians would have their underground supply of ddC cut off — this ddC was being manufactured for American patients, and the tiny Australian market was negligible.

In truth, Jim Corti had told me that, while he didn’t know how, he would not let Australian patients down. He said US buyers clubs were already contemplating continuing to sell ddC even after approval, and this would have needed Jim to continue manufacture. Unlike Australians who would have their ddC paid for by the government, many Americans without health insurance could not afford Roche’s ddC. The underground ddC would join the other drugs that buyers clubs brought in – from Mexico, for instance – not because they weren’t available in the US, but because they were just cheaper that way, given how multinational pharmaceutical companies set prices based on local market forces, i.e. the top price that market can bear.

But Jim knew that continuing to manufacture ddC post-approval would be the most dangerous move of all. Unlike other buyers club drugs that had been sold for years before they were imported or bootlegged, ddC was a brand new drug for Roche and the company hadn’t even started recouping its development costs. No way would it countenance bootlegging post-approval. And Jim had repeatedly said to me that he wanted to stop once the US FDA approved the drug. Which is also what Marty Delaney (of Project Inform), the activist Jim worked most closely with, said in public.

But back to the Australian situation. I was adamant that either the drug company or government pay for it. Not, once again, a community near death looking after its own. That’s why I said what I said in the speech. Once the FDA approved ddC in the US, I approached Roche Australia and said, I need you to supply ddC for my 400 patients until TGA approval in Australia.

Looking back, I am a little amazed that Roche agreed to it. Had it not been for Michael having gotten close to me and then his advocacy within Roche Australia, this would not have happened. I had one of those ad hoc alliances with Michael and his boss David Kingston, because we had a common purpose: getting Australian approval for ddC as soon as possible. So I assisted them where I could. I wanted Roche to submit the FDA’s report to the TGA here to accelerate the local approval. But Roche didn’t have the report. It was still winging its way from Roche’s US office in New Jersey. So I said I would get it. I called John James – founder of AIDS Treatment News, the indispensable newsletter for any person with HIV. Of course John had it — the ace investigative medical journalist that he was — and he faxed it to me, all 400 pages. I sent it to Michael and that’s how Roche Australia got the FDA report.

It was in this makeshift spirit of cooperation that Roche supplied ddC to the buyers club’s clients in Australia, which, as far as I know, did not happen anywhere else.

The quantity of ddC needed was comparatively small — I had only 400-plus recurring clients. Which brings up another point: the reason that only 700-plus people in Australia got ddC through a buyers club. In fact, thousands of Australians were on ddC, but they got theirs via the clinical trials or the open-label program. Some genuinely could not tolerate AZT anymore. Some just lied and stayed on AZT when they weren’t suppose to. When a new client showed up at the buyers club, I did my best to first place them into the open-label program — find them a new doctor, if their present doctor was too chicken to apply for their enrolment. Official ddC was always preferred. Buyers club ddC was a last resort.

Today, ddC is no longer used in the treatment of HIV. AZT still is. As is ddI, though very rarely. But not ddC, the drug that was the centre of a massive patient empowerment movement. About 15 years after the events I’m recounting, ddC was withdrawn from market. It brings me back to my point in Dextran Man, Part 1, that the buyers club were noble failures. Despite our hopes, ddC was not going to save lives permanently. It delayed death. It did this substantially enough that some people were still alive when the protease inhibitors, the first drugs that could be said to save lives, arrived.

Mortality is era dependent. I find myself still occasionally thinking about the ddC cohort – both the buyers clubs clients and the expanded access program enrolees – especially the ones who went on to protease inhibitors. And of those, who lived and who died. Because some were too sick by the time they started protease inhibitors. The drugs’ Lazarus Effect – as we called the rebound from death’s gutter – was astounding, except for those for whom it was too late.

There have always been people who became ill at the cusp of treatments and cures. And it’s almost happenstance whether they can be treated successfully.

The world recently saw the cure, and I use the word without qualification, of a major viral disease – Hepatitis C. Those who had early access, whether by being activists or patients of activist or research doctors, got the cure in 2011. By 2013, it was generally available. This two-year span mirrors 1994-1996 in HIV — the well-connected got protease inhibitors in 1994; by 1996 the drugs were standard therapy.

George Michael and Evel Knievel, had their Hepatitis C illness started later or they somehow lived into the cure era, could have survived. I suppose this disease came to mind as an example because Australia has a cultural association with hepatitis. One of the earliest markers of hepatitis B infection was discovered in the blood serum of an indigenous Australian. Scientists called this the ‘Australian Antigen’ and it was the basis of the first generation of hepatitis B assays and vaccines.

Australians also ran a Hepatitis C buyers club once the cure drugs became available. But unlike the ddC buyers club, this was not about gaining access prior to regulatory approval. It was purely about expense. The Hepatitis C buyers club transgressed the law by distributing a generic version of the drug, illegally made in India, because the official drug was priced outside the affordability of many patients. It was a glimpse of the road not taken, had Jim Corti defied Roche, FDA and TGA and continued supplying ddC post-approval.