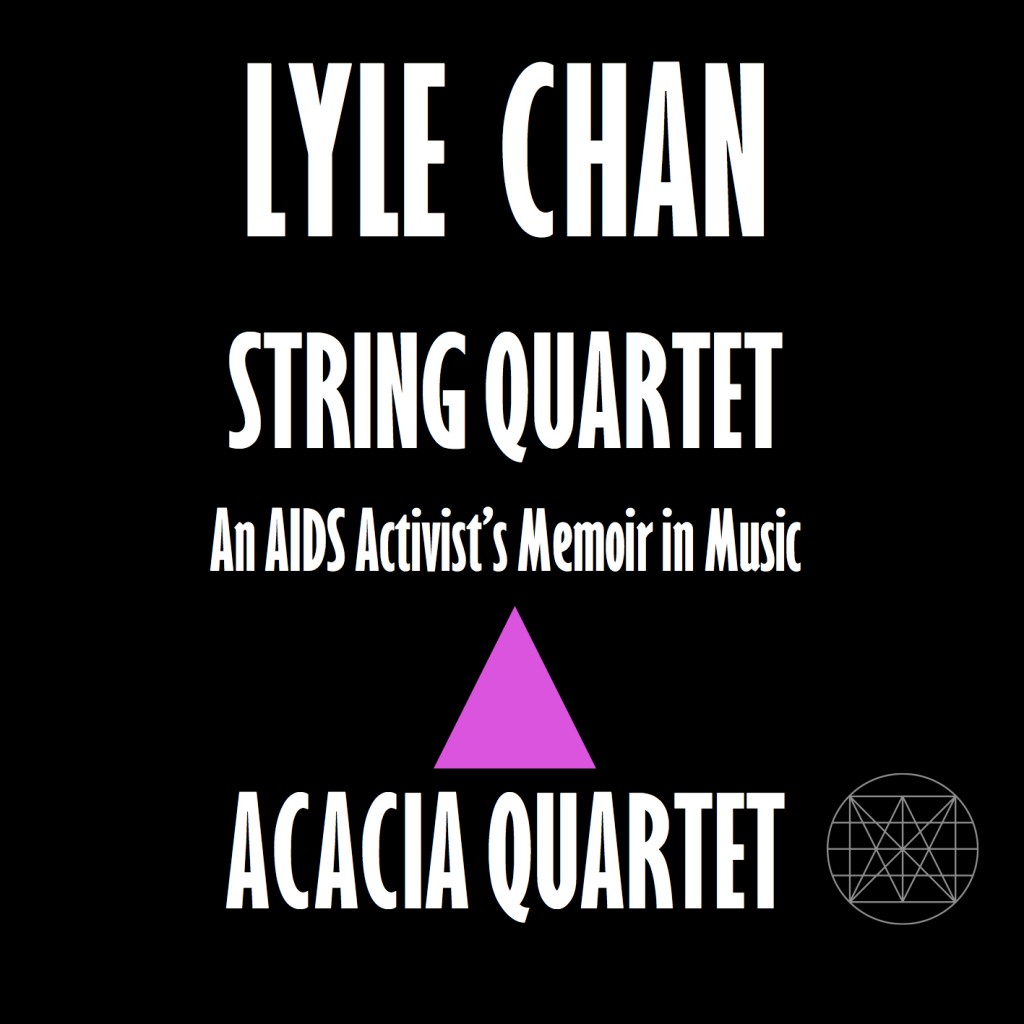

For the past 2 years I have been writing a string quartet fleshed out from the sketches I wrote while I was an AIDS activist in the 1990s. The music has now been recorded by the incomparable Acacia Quartet and released digitally on ClassicsOnline, iTunes and a myriad of other online stores. And though various excerpts of it have been performed in concert, the first ever performances of the entire work will take place in July. Announcements about these concerts will be made soon.

The booklet that accompanies the recording contains brief versions of a set of essays I’m also writing, a parallel memoir in words. But there’s so much to say that it’s taking me a while. So please make do with the short versions for now. Meanwhile, I’m publishing the few essays which I have completed here on this blog.

The very first essay, to accompany the music In September the Light Changes, is below. You can hear the music using the Spotify player above.

___

My story as an AIDS activist in Sydney began when I was still living in Madison, Wisconsin. My first boyfriend, Geoffrey, whom I met when I was 21 in 1988, was HIV-positive. Mine was the first generation of gay men who never knew a time before AIDS.

It’s been such a part of my consciousness that I can no longer recall when I first heard about AIDS, though it would have been in the context of obscene jokes enjoyed by my fellow high schoolers. What I do remember was that I already knew what AIDS was by the time news broke about Rock Hudson, and that was mid-1985 and I was 18. After the Rock Hudson scandal, there was pretty much no one left who hadn’t heard about AIDS.

I was a gay teenager who was growing up under the impression that being gay and living with AIDS meant the same thing, yet it was all impersonal to me. Then around Christmas 1988 I met Geoffrey in a gay bar in Madison called Rod’s. I had come from some church function (I was pianist and organist at the university’s Catholic center called St Paul’s) and was wearing an improbable three-piece grey suit. Then as now, I rather liked formal clothing. I didn’t so much like the appearance intrinsically so much as I liked the way it made my formal bearing, rather incongruous in a teenager, more excusable. Geoffrey was bemused. We bought each other drinks, mine rum (always Bacardi) and coke, his beer. He made suggestive jokes about the suit and what I may look like underneath all those layers of wool and cotton.

Geoffrey was the foreman of the local bagel bakery called Bagels Forever. He was mysteriously English in origin though he’d been living in the USA for practically his whole life. And he was the son (technically stepson) of the composer Robert Wright, half of the famous songwriting team with George Forrest responsible for Broadway hits like Kismet and Song of Norway. I found that out not the night we met but after we started dating. What he did tell me that night was that he was HIV-positive.

Geoffrey was 9 years older than I was. My relationship with him wasn’t particularly serious, mostly because Geoffrey kept me at arm’s-length and never gave it a chance, and I didn’t know any better because he was my first boyfriend. He’d insist we go for days without seeing each other, and he would deliberately not return my phone calls because he liked it, he said, when I “got cross” with him.

Geoffrey shared an apartment with a young guy named Walt. Walt wasn’t just HIV-positive. He had that emaciated look that I learned to recognize as someone with AIDS. Walt stayed home all day, often in bed. Once I saw Walt with an IV drip. They’d been friends for a long time, and I’m pretty sure they used to be boyfriends. Walt was very kind to me, and I think I learned as much about Geoffrey from Walt as I did from Geoffrey himself. Walt understood my frustration with Geoffrey’s distance. I didn’t even think Geoffrey’s coldness was a way of protecting me, but of course, that’s what it was. He was HIV-positive in a world where you’ll inevitably get AIDS and die. Walt was going to die and Geoffrey was going to die. Where in all that is the point of young men falling in love?

As a gift to Geoffrey I wrote him a piano piece (I wince to recall this, but I even titled it an Ode, which made Geoffrey hee-haw with laughter), and it contains one of the most beautiful melodies I’ve ever had the privilege, then or since, to compose. Such was the pressure of dating the son of Robert Wright. I used the pulpit microphones installed in my church to record myself playing it onto a cassette tape. The day I gave him that gift was the only time I saw him let his guard down and his eyes soften and water. I could see plainly what he was thinking, if only it didn’t have to be this way.

My instincts tell me that Geoffrey is dead now but I don’t strictly know. When I decided that Geoffrey was intolerable because of his insensitivity to my feelings (or so I selfishly thought), I left the relationship, and didn’t keep in touch.

Before Geoffrey, AIDS was theoretical to me. But then, before a first boyfriend, gay life itself was kind of theoretical anyway. After Geoffrey, I saw it everywhere, as if I had been slapped awake. Even the early stages of AIDS-related illness, seemingly undetectable at an ordinary glance, I recognized instantly. I saw it in the bars. I saw it in the bookstores. I even saw it in church. The university’s gay support group (lovingly named the Ten Percent Society) had a president, younger than me, who was HIV-positive though still asymptomatic.

“Aren’t you a little young to have lost a lot of friends to AIDS?” That was a question out of the blue from Peter, a man I was dating in 2003, many years after the magical fairy-tale ending that we now know is how the crisis finishes. Peter was two years my senior. We’d been talking about our youth and mine seemed anachronistic to him, like I was describing the early-20s of a person a good deal older. And he was right. Most people with AIDS and their peers were a good 5-10 years older at least. As I already said, mine was the first generation of gay men who didn’t know a time before AIDS. The ones who did know, those were the ones who got AIDS — because it was a time when people hadn’t realized a virus or a fatal infection was spreading, a time when the worst thing you could get from unprotected sex was gonorrhea or herpes or syphilis, all of which modern medicine triumphantly cured; a time before the prevention education and safe sex campaigns and before behavior changed.

The reason I had the AIDS experience of a person older than my actual years was, funnily enough, my dating preference. I liked men, not boys. I wasn’t attracted to boys my own age. I was attracted to men who were in their 30s. They’d be who I’d hang around. It wasn’t unusual for me to be the youngest person in a social group. And gay men in their 30s in the 1980s was the AIDS prime demographic. That’s the reason I wasn’t too young to have lost a lot of friends to AIDS. So AIDS exploded around me. I didn’t know what to do, but I also knew I couldn’t do nothing. I was young enough to change careers if that’s what it took. I even thought about being a doctor. Then I said to myself, I could at least educate myself while trying to decide.

I was still pursuing my Bachelor degree at the University of Wisconsin. I had the immense good fortune of studying anything I wanted. The university just took your word that you were interested. Prerequisites were few; no one had to jump through hoops to enroll in a class, though passing one was an altogether different matter. I had been studying composition under Conrad Pope, Beethoven under the legendary Pro Arte Quartet and Charles Ives under J. Peter Burkholder. But now I enrolled in a molecular biology class taught by Howard Temin, the Nobel Prize-winning co-discoverer of reverse transcriptase, the enzyme used by HIV to replicate itself.

One of his associates, Rex Risser, had a postdoctoral student named Eric Freed who needed a laboratory assistant. I convinced him and Rex that I, who’d never been inside a molecular biology laboratory, would be great at the job. Eric was conducting research on the role of the glycoprotein outer layer of HIV in entering a human cell. I was helping determine the genetic sequence of this outer layer using gel electrophoresis. Eric, a straight good-looking young man with wild hair and slightly tamer mustache and beard, developed an extra affinity with me because he also had a passion for classical music and was a fine violist. Once after dinner at his place we played through every single sheet of music he had for viola and piano. Eric’s now the head of a major division of the HIV drug resistance program at the National Cancer Institute. I’m sure it was Eric’s influence that unconsciously made me assign the long tune in this piece to the viola.

There was already a growing grassroots movement around AIDS, antagonized and fueled by the Reagan administration’s abominable neglect of the disease. The President’s personal indifference to the disease (his years of silence on the topic despite repeated calls by doctor groups and patient communities for a strategy on AIDS) and disdain for gay people (despite he and Nancy having been good friends of Rock Hudson) — all this legitimized a whole nation’s fear. It’s hard to describe this to today’s changed world, but as L. P. Hartley said, the past is a foreign country and they do things differently there. The 1980s was a time well before mainstream gay invisibility. Geoffrey and I felt the historic monumentality of the moment as we watched the now-legendary episode of the prime time TV series Thirty-something featuring a gay male couple in bed after sex, with the actors strictly forbidden to touch each other or the network would not air the episode. The actors were so wooden out of fear of accidentally touching one another.

In 1987 the grassroots movement formed its most visible, loudest nucleus — the radical direct action group ACT UP created itself in New York in 1987; soon it inspired local chapters to form in cities across the country, and I helped found its Madison chapter in 1989. But in Madison, we were too far away from places like the National Institutes of Health to influence government research agendas, too far away from the headquarters of pharmaceutical companies to influence drug trials. All we could do was focus on prevention education. It was an early lesson for me that action around the crisis would be divided into two branches: those who would help prevent transmission to healthy people, and those who would help the sick get treatment. There would, I later learned, always be tension between the two.

All this while, I was a student technician in a laboratory that focused on basic science. The very nature of basic science is about answering fundamental questions — how does HIV dock with and enter human cells? How does it turn a human cell into a factory for more virus? How the answers became therapeutic medicine was someone else’s job, not that of a basic scientist. I was torn between the sure need for basic science research and my growing personal impatience at needing to see life-saving results more quickly.

The music I wrote that eventually became In September The Light Changes was sketched in both Madison and in Sydney. In late 1990, I was at a crossroads in my life. I had graduated from the University of Wisconsin with a degree in physics, a not insubstantial amount of practical experience as a molecular biologist, and enough of the pre-medical track under my belt to apply to American medical school if I’d wanted. I also had a lot of privileged, almost elite musical training; in a world without AIDS I possibly would have decided on a career as a composer right away. At a complete loss, I decided to go visit my parents and brothers who had all emigrated to Sydney, Australia from our original home of Malaysia. I’d be the last to join the family; this was Christmas, 1990.

In Sydney, I discovered that the local gay community had created its own ACT UP chapter only a few months before I arrived. The trigger issue was access to AZT, the only drug formally approved to treat HIV infection. While people with AIDS could obtain the drug, people with asymptomatic HIV infection who wanted to delay the onset of AIDS by taking the drug, couldn’t, not according to the slow due process of the Australian government. This was the touchstone issue that created ACT UP in Australia, which it successfully solved in tandem with other AIDS groups by using public demonstrations and public opinion to embarrass the government into prompt action. This first victory had galvanized the local activists, and it was this confidence that greeted me as I attended my first ACT UP Sydney meeting in January 1991.

I sketched part of this music as the new year began, thinking, I travelled thousands of miles, and made new friends in a new city, and they have AIDS too. It really is everywhere. The music that was written in Madison was an observation that my world was on a cusp between, at best, precariousness and, at worst, who know what — maybe annihilation. I wrote a music of fluids — mists and foghorns, half-light and rain. I’m sure it’s because of the new year, but the music solidifies into a churning melody, the original tune that Robert Burns had in mind when he wrote one of the greatest poems ever about friends, Auld Lang Syne. Friendships should have the chance to grow old, but maybe not today. Against the tune, bombs fall from the sky, distant explosions heave the landscape and yet the only people who can hear them are those doing the fighting. It’s as in any war.

My title, In September The Light Changes, was both a literal observation as I travelled to another hemisphere and, as I’ve since discovered, exactly the title used for a story collection by Andrew Holleran. In the 1980s he wrote a column in Christopher Street magazine, intended as an observation of New York gay life in all its frothy playfulness, that turned inexorably into a chronicle of the AIDS epidemic.

In 1991 it was hard not to notice the light changing as if it were the autumn or twilight of a whole people.