When I wrote the first set of memoir essays, starting in 2011, there weren’t that many AIDS memoirs. At least not ones written post-crisis.

During the plague years, important memoirs were written. There were searing ones like Paul Monette’s Borrowed Time about living and dying with AIDS, and similarly Timothy Conigrave’s Holding The Man, the most well-known of memoirs in Australia due to its subsequent dramatizations.

There were also other factual accounts like the journalistic books about the search for effective treatments, like Peter Arno and Karyn Feiden’s Against The Odds and Jonathan Kwitny’s Acceptable Risks.

These were all written in the white-hot period when holding hope was, let’s be honest, an irrational choice.

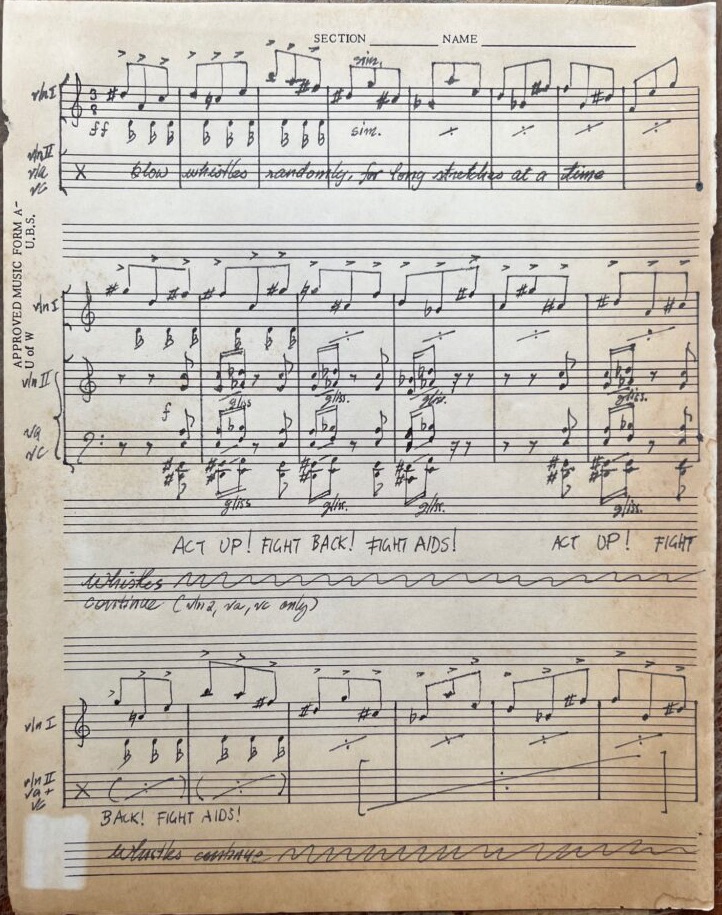

But when the miracle drugs came — and they came at different times for different people, between 1994 and 1996, depending on how connected you were to people giving out experimental drugs — the plague years were over, just like that. Yes, just like that. Everyone still left standing raced forward with their lives. Some raced to do things they couldn’t during the plague years, like me who finally allowed myself the frivolity and solemnity of writing music. Some raced into the unknown and didn’t like what they saw; their purpose had been defined by a fight and now that the reason to fight was gone, so was their purpose and reason to live. I had friends like this, warriors who needed a war. People miss you, Bill.

But in all this racing, no memoirs got written, not for a long time. It would take a good 20 years for us to collectively absorb the sensation of after-plague.

It’s hard to say why this was. For some people, it took a long time to fade, that niggling sense of what if it isn’t over, what if we were wrong and it or something like it comes back. It took 20 years to believe we weren’t jinxing our good luck by talking about it like it was over.

For some others, probably me included, it took that long to feel we’d made up a little for the lost time, for having done enough of what we couldn’t do during the plague years that it was finally all right to do idle things like strolling down memory lanes.

And now some fourteen years since I wrote my first essay, there has been an outpouring of memoirs from AIDS activists. To mention only the ones from the ‘mothership’ ACT UP New York, Peter Staley’s autobiography and Sarah Schulman’s ACT UP history came out soon after the Covid-19 pandemic hit. I also want to mention Sean Strub’s older autobiography because its release coincided with that of my string quartet memoir some ten years ago, so we met and chatted at the 2014 International AIDS Conference; I remember being struck, not for the first time, by how parallel were the lives of ACT UP activists around the world, how the allies and foes were by nature the same and only their names were different.

The new memoirs brought about and were brought about by an interest in this history. I get asked often enough for interviews that I don’t have time to accept them all. Sometimes the historians and journalists are knowledgeable, and sometimes they’re not. Sometimes they’re respectful, and sometimes they’re not.

There comes a time in every history when it will be written by those who weren’t there.

Facts are incontestable, but what people call truth, being an assemblage of facts, is subjective. This is because every time two or more facts are associated, the issue arises as to why those facts and not others were chosen, as to what the motivational reasoning is and therefore what the narrative, being a constructed view of events, is behind the choice of facts. When I understood this aspect of historiography, I understood why people use phrases like “my truth” – there are in fact many ways to tell the truth. Every telling can be true and yet one person’s truth may not ring true for someone else. I say this to remind myself to be generous, because I sometimes read accounts of events I lived through and I don’t recognize them. When I’m generous, I acknowledge that the collected works of our history are an aporia, i.e. in an undecided state; when I’m not generous I say the ones that contradict mine are plain wrong. I’ll return to this point.

A couple of years ago I was interviewed for the ABC documentary Queerstralia, and the interviewer, who was a professional comedian, said that my string quartet is like the AIDS quilt. She meant well, but I was put off by the maladroit comparison. Still, how could she, born so long after the plague years, understand that there is a fundamental difference between making a memorial during the crisis and making a memorial after the crisis. In the crisis years, there was barely enough time to attend funerals, let along stop work to sew a damn quilt. ACT UP Sydney never stopped to make quilts.

But after the protease inhibitors, whoever was left standing was entitled to make quilts and write memoirs.

In German, the words for monument and memorial are the same, yet the word has two plurals: Denkmale and Denkmäler. Both are correct; the writer has a choice of two truths. This came to mind as I was thinking of the Austrian author Robert Musil’s famous observation that there is nothing in the world as invisible as a memorial. Not only are they not noticed, but memorials have a quality that actively repels attention (his original is stronger: verscheuchen, literally to scare away).

Quilts and memoirs the same yet different, like Denkmale/Denkmäler, and similarly hard to linger on. Certainly the subject matter here –people who died deaths that were preventable if it weren’t for apathy and discrimination – is repellent.

I have found that I am neither happy nor unhappy to tell the stories. If a memorial has that quality of actively driving away attention, then that quality must come from the process itself of making the memorial. We the storytellers are the first repulsed. Personally, I’d rather distract myself with anything than write the stories of the plague years. And yet despite our best efforts to find diversions, Musil’s monuments get made, and the plague memoirs get written.

And this brings me to the reason I’m revisiting the plague years ten years after I released my string quartet memoir. The memoir essays were written for a general audience. I left out a lot of detail because I didn’t think, when I started back in 2011, detail would interest anyone. Not only that, but the original set of memoir essays is incomplete. I started with things I knew only I could write about, and I never got to the rest, partly because there started to be all these books and documentaries and movies about the plague years.

Which brings me back to the contestability of truth. In these accounts, I found that I always recognized the world when it’s depicted by a participant or an eyewitness. But when the depicter is someone who wasn’t there, too often I don’t.

I had been told about the movie Dallas Buyers Club about four years before it was released and I was really looking forward to it. I really wanted to like it because it was about Hollywood paying attention to this history. But the movie didn’t have the ring of truth about it. In the pursuit of good storytelling, the entire context got left out, as if Woodroof was the only person doing what he did and there was no AIDS activist movement and no Jim Corti. I don’t understand why Woodroof was depicted as a homophobe. Jim worked fine with Woodroof and I don’t recall Jim ever saying anything bad about him. At no point could I forget that this was a work of fiction. Dallas Buyers Club was the disappointment that started me thinking that those of us who were there had to continue to tell our stories.

There’s this biography of an activist friend of mine who died during the AIDS crisis. The biography was written many years later by a family member who wasn’t always close to my friend. It’s sold as a biography but actually the book is written as novelistic nonfiction, Truman Capote-style, with imagined dialogue and reconstructed events just like In Cold Blood has. I found the activism accounts really hard to read. As with any of the books or documentaries, whenever the gist is right but details are wrong, I can ignore the errors. But the biographer had turned my friend into a Forrest Gump character who shows up at every historic AIDS event, even those before his time. I feel churlish thinking these things, as this was a biography written out of a decades-long grief for having outlived him when it should have been the other way around. Still, I can’t help feeling dismayed that historians later on will take at face value some of these dramatizations of ACT UP meetings and demonstrations that ascribe words and actions to real people’s names but who are actually conflated characters.

There’s more, including a book published by a university press that has no source notes and is unverifiable. Rather than wish that such specious books or films not exist, I actually think the antidote is for there to be a plethora of histories, so that people can read across the inconsistencies and arrive at an overall broadly accurate impression made possible by a larger sample size of accounts. I include the things I’ve written as being subject to errors of memory, emphasis, etc and I do my best to not be definitive when I can’t be. I wish that the family biographer of my friend could have done the same, and I wish Nick Cook could have done the same in his book Fighting for Our Lives and I‘m glad Dallas Buyers Club at least did the right thing by not denying that it is fiction.

Ultimately I’m lamenting that there aren’t enough people leaving stories behind, and I can’t be exacerbating the dearth if I can help it. Garance Franke-Ruta was reproached by someone who’d discovered she hadn’t put on record her experiences in ACT UP and Treatment Action Group at the height of the crisis. “Others would talk about such experiences all the time,” they said. “Not if you lived through it,” was her response, and in it I heard loudly my own reasons for not talking about it for 20 years. I too would gladly have kept tacet, the situation having reached a point where silence no longer equals death the way it used to. Maybe I would have, had ACT UP Sydney more remaining people to tell its story. Actually I simply wish ACT UP Sydney had more remaining people – survivors, veterans – regardless of whether they want to speak.

I’m told that one of the reasons we should write our histories is so that young people – young gay men specifically – can learn about the past. I meet young bisexual and gay men all the time who don’t know this history. They take PREP and have no idea how this pill came about, no idea of the people who fought and died fighting to bring about the drugs that saved lives, the same drugs now used to prevent infection. And yet. I know this is not a popular opinion, but personally I have no issue with young gay men not automatically knowing the history of AIDS. That history should be documented and accessible for anyone who wishes to learn it, but kids don’t need to be compulsorily and inexorably burdened by a dark past, an inherited trauma passed down over the generations. I hope being unencumbered they have the choice to lead lives that are lighter and more carefree, maybe even frivolous. Frivolity and solemnity. Two of the ingredients for living life. One of them wasn’t around during the plague years, and I’d be fine for it to be part of young people’s lives now.